We here at the Map Scroll would also like to endorse the ironic detachment of Von Worley's post - such a mood being really the only way to cope with the bombardment of consumerist waste the US landscape has endured over the course of the last 60-odd years - which begins thus:

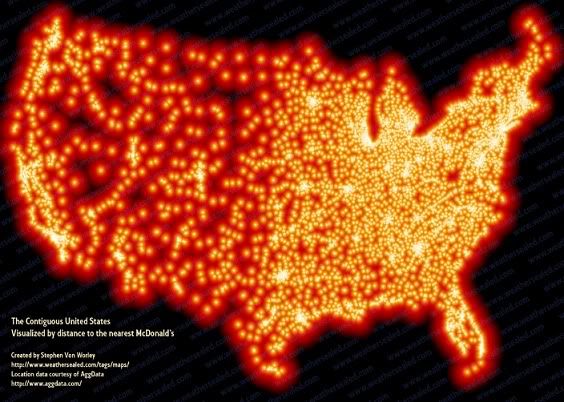

This summer, cruising down the I-5 through California’s Central Valley to the Los Angeles Basin, I unwittingly stumbled upon a most exasperating development: the country strip mall. First, let me state that I don’t hate. I’ve got nothing against Petco, Starbucks, OfficeMax, et al. When overcome by the desire for a cubic yard of kitty litter, a carafe of pre-Columbian frappasmoochino, or fifty gross of pink highlighter pens, I’m there in a jiffy!He got data on the locations of all 13,000 McDonald'ses in the lower 48, applied some "technical know-how," as the kids call it, and made this map. As you can see, there's really no escaping the Gilded Parabolas in the eastern half of the country. There are, though, a few pockets in the West where the hegemony of the arches needn't weigh quite so heavily on the spirit:

But, Mr. Real Estate Tycoon, did you have to plop your shopping center smack dab in the middle of what was previously nowhere? Okay, the land was cheap. And yes, you did traffic studies and proved that the interstate and distant suburbs would drench whatever you built in a raging torrent of eager consumerism. But your retail monstrosity drains the wildness from the countryside for twenty miles in every direction! Sure, you can’t see it from everywhere - but once you know it’s there, you feel it. In the rural drawl of a neighboring rancher, that flat-out sucks!

Which begs the question: just how far away can you get from our world of generic convenience? And how would you figure that out?

For maximum McSparseness, we look westward, towards the deepest, darkest holes in our map: the barren deserts of central Nevada, the arid hills of southeastern Oregon, the rugged wilderness of Idaho’s Salmon River Mountains, and the conspicuous well of blackness on the high plains of northwestern South Dakota. There, in a patch of rolling grassland, loosely hemmed in by Bismarck, Dickinson, Pierre, and the greater Rapid City-Spearfish-Sturgis metropolitan area, we find our answer.I'm totally moving to Spearfish.

Between the tiny Dakotan hamlets of Meadow and Glad Valley lies the McFarthest Spot: 107 miles distant from the nearest McDonald’s, as the crow flies, and 145 miles by car!

Via Felix Salmon.